Fixed income has traditionally helped to build resilience in diversified pension portfolios in times of elevated stock market volatility.

Bonds came to the rescue for multi-asset funds when stock markets fell in the dot com bubble of 1999, during the global financial crisis of 2008, then in late 2018, when trade tensions between the US and China escalated, and most recently at the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in the first three months of 2020.

Government and corporate bonds have also served their purpose in risk-aware retirement strategies of helping to reduce the risk that customers are exposed to in the closing stages of their retirement savings journey by providing a modest but positive return.

But since the start of the year and, in particular, in the three months to the end of June when bond and equity prices declined and the performance of equities and bonds has become more closely correlated, the traditional role played by bonds in a diversified equity/bond portfolio has been questioned.

We’re in a highly unusual market environment though, caused by an unprecedented set of circumstances: a persistent rise in inflation, accentuated by the conflict between Ukraine and Russia, has triggered fears of a global recession, all on the heels of a global pandemic.

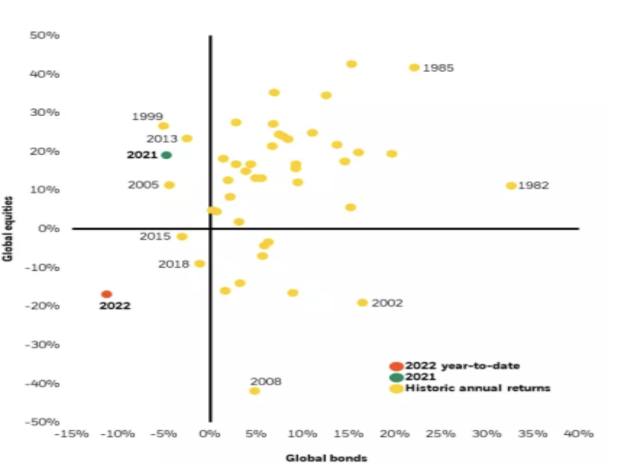

There have only been three years in the past 45 years where global equities and bonds have sold off at the same time, as shown below.

On this basis, we believe that the market dynamics for bond investors will reassert themselves eventually.

The very real risk of a recession also means that central banks could at some point reassess their tightening cycle, which would in turn support bonds.

Central banks have responded to the sharp rise in inflation by tightening monetary policy and so raising interest rates and paring back their bond-purchase programmes.

This stance by policymakers, while anticipated in 2021 and thus causing volatility in bond markets, nevertheless created a massive shock for markets and for the economic system after 10 years of record low inflation and interest rates, and the adjustments in bond prices since mid-2021 are a reflection of this.

Central banks are caught in a tug of war, needing to fight inflation without creating more problems for the economy.

The International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the OECD have all warned in recent months that we face a global recession due to the war in Ukraine.

The US central bank has taken a more aggressive approach to raising borrowing costs than its peers, taking rates from near zero to a range of 2.25 per cent to 2.50 per cent since March, while in the UK, where rates are 1.75 per cent (as at time of writing), the Bank of England has been criticised for not acting sooner on inflation and also for not raising borrowing costs enough.